The Cabinet Office Technology Transformation programme was set up in late summer 2013. Our primary mission was to replace the Cabinet Office’s current IT system with modern and flexible technology that’s at least as good as that used by people at home.

During a very short time, we needed to find alternative solutions for devices, internet connections, printers, mobile phones, networks and more. The project was ultimately not just about new shiny devices, but about providing useful and usable tools to help people work better.

How it all started

I’m a user researcher, and I joined the project team 12 months ago, at the very start of the programme. We wanted to make sure that user needs were taken into account from the very beginning.

It’s a year in, and we’re now preparing the Cabinet Office for the full project roll-out.

In this post, I’ll share what we did and how user research fitted into our approach.

Becoming a part of the wider team

Based in the Cabinet Office’s building in Westminster, our team began with 2 desks in a tiny corridor, squeezed between printers and boxes of paper. We were thrown right into the middle of the Cabinet Office.

Working in the Cabinet Office was perfect in helping me quickly move from being an outsider to someone participating in the same organisational culture. A part of the crew.

We shared the same canteen as the Cabinet Office staff and struggled with the same office issues, like getting a building pass for a new starter. We attended staff meetings and community building events.

Because we experienced the same things as our users, we were able to understand what it meant to work inside the core Cabinet Office. I was also able to put on my ‘user researcher hat’ to interrogate and understand it in depth.

Asking the right questions

Technology, like any other tool, is supposed to facilitate what we need to do at any given moment. With this in mind, before asking the question:

What technology do Cabinet Office users need to have a better life at work?

We decided to ask:

How does it feel to work in the Cabinet Office?

It was obvious we had to start with people.

Having a broader perspective

I started talking to our users about their experiences at work, personal goals, motivations, challenges and attitudes towards the tools around them. These conversations weren’t only work related; we wanted to understand who our users were before finding out what they did in the office.

I shadowed people at work, observing who they worked with, how they tackled problems and how they spent their free time. These lengthy sessions helped us grasp aspects of the environment not mentioned during interviews, perhaps because users considered them obvious. Shadowing people gave us a more thorough understanding of what was going on ‘behind the scenes’.

We invited people to participate in creative workshops where they could express themselves in spontaneous and (hopefully) fun ways. This allowed our users the opportunity to detach from their current reality and to think about an ideal world with no technical and legal constraints.

Finally, we gave our users a chance to test applications and devices, which we thought could help them. This gave us the opportunity to gauge well in advance whether our assumptions were right or wrong.

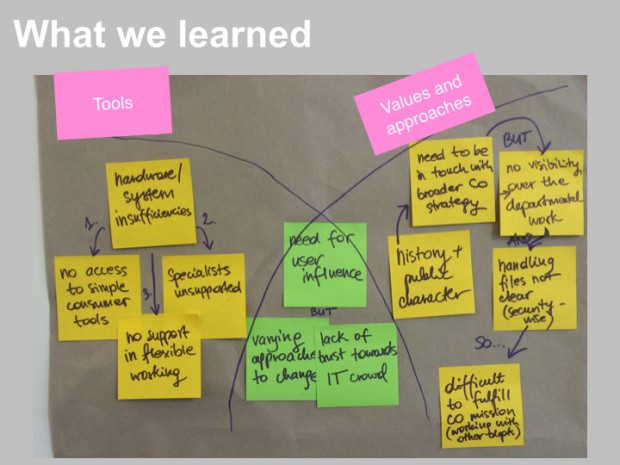

What we learned: uncovering the basic principles of our ‘mini culture’

By analysing both similarities and differences between people’s behaviours and attitudes, we were able to uncover the basic principles of our ‘mini culture’.

Issues that seemed unrelated, such as, lack of effective video conferencing tools in remote Cabinet Office locations and no easy way of sharing documents between teams, became signs of broader organisational values and approaches.

We analysed everything we were learning about the people we were cohabiting with, and the world of the Cabinet Office became more clear.

People who work here want to participate

The Cabinet Office is a place full of history and public significance. As an example, a regular 'History Week' organised in its main building invites employees to learn about the history of the institution, take a peek into 'secret' corridors, see old documents and participate in lectures and workshops.

People who work here want to be in touch with a broader Cabinet Office strategy and are proud to be a part of it - they want to participate in learning and development courses and stay updated with departmental changes.

Promoting sharing of information inside and outside of teams can be facilitated by tools, which enhance the collaborative character of the departmental work.

The use of personal devices is prevalent

The Cabinet Office encourages users to work more flexibly, for example, split their time across different teams and work remotely. Dynamic environments pose big challenges in terms of technology. As a result, the use of personal technology among users is prevalent.

Personal mobile phones and tablets help users organise their day and work on the go. Understanding this allowed us to understand which user needs we needed to target first.

I use my own tablet, especially when going around to meetings. It helps me to take notes. Our team is always moving around, we do a lot of fieldwork and meetings outside of this building, we are never here, so it’s helpful.

Need to influence the design of their work environment

Research taught us that our users, as a whole, wanted to have influence over the design of their work environment. There were, however, varying attitudes towards change across the organisation. Some users were more eager to revolutionise the way they work, while others were more reluctant.

Also, inflexible devices, unstable services and sometimes unhelpful support, resulted in a lack of trust in IT and those who delivered it.

I would like to work in an open environment, where we don’t have closed doors and anything that slows you down.

Developing trust

Due to both past and current experiences with technology, people stopped trusting the ‘IT guys’. Thanks to the programme’s focus on user needs, we’ve looked into how people work and what they need in much more depth than similar projects have in the past.

It will take a lot for our users to trust CO technology once more but hopefully, by getting to know them and responding to their needs, we’re taking a big step in the right direction.