Amy Everett is a senior user researcher at the Home Office, working in the policing team. The policing team is a multidisciplinary team that work with police forces across the country to help design better digital systems for the police and the public. Amy recently worked on a discovery looking at fixed penalty notices (FPNs).

Around 2 million fixed penalty notices (FPNs) are issued in England and Wales every year. Most people will know them as a speeding ticket, but they are issued for a wide range of traffic and motoring offences, including driving without insurance or not wearing a seatbelt. Drivers who are issued a fixed penalty notice can usually either go on an awareness course, pay a fine or challenge the offence in court.

The discovery team I recently worked with were asked to look at the police system that holds the national FPN information to see how it could be improved, or what a new system might look like in the future.

We felt this scope was quite narrow, so together with our stakeholders, we broadened the scope to properly understand the end-to-end experiences for police and the public.

As Jared Spool recently wrote: ”We’re now in a world where digital and non-digital are merging. And we need to be prepared to design in that overall experience.” We needed to be able to research in that overall experience, in order to be able to design for it in the future.

Spending time with our users

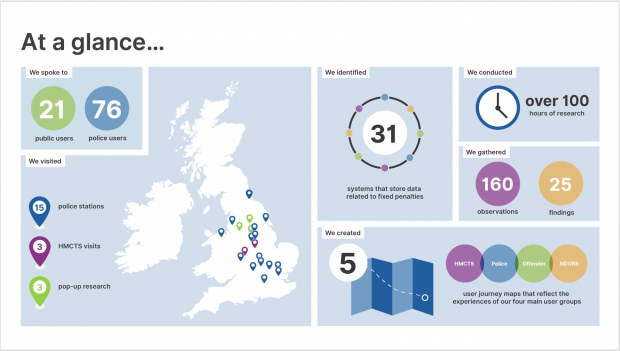

During the 3 months of our project, we conducted over 100 hours of research, speaking to 21 members of the public and 76 police officers and staff.

We spoke to the public about their experience through the whole process and about how they decided what action to take after receiving their fixed penalty notice. We also spent a day in our usability lab with people who had access needs, looking at one of the letters sent to offending drivers. Spending time researching the letters was important to us as we wanted to understand if people could understand them, and how they used the content of the letters to make a decision about what to do next.

We used a combination of semi-structured interviews and pop-up research to find users to be participants in the research – with varying success. Pop-up research for police-related matters was much more difficult than we thought it would be, but that’s a story for a whole other blog post!

However, the primary focus of the research were police staff who issue and process fixed penalty notices. We conducted contextual inquiries with 15 different police forces across England and Wales.

To do this, we went right to the start of the journey for police, spending a day with officers on an operation to pull over any drivers that were seen to be committing a road offence. We were able to interview the officers and ask them about their processes and also observe them in action.

We also spent time with users in their office environment, where they input the ticket information into their systems, sent letters and received responses from the drivers. We didn’t want to just see each task done once. We spent hours with staff as they went about their jobs, watching how some tasks were more difficult than others, how the team communicated with each other about particular cases, and how each system being used had its own intricacies depending on the type of case being dealt with.

We found that, for police staff, an incorrectly positioned button on a system’s manual input form isn’t just a problem once a day. It’s something they have to work around between 20 and 30 times a day, or 150 times a week. It’s a design issue that affects the user’s full-time job. The system, and how it makes them feel, is part of their lived experience.

“Understanding users in terms of their whole experience of a technology, especially how they make sense of it in the context of use, by considering the emotional, intellectual, and sensual aspects of their interactions with technology … the importance of understanding how people do not just use technology, but that they also live with it.” – Research in The Wild, Rogers (2017).

Never assume

Spending extended periods of time with our users meant that in our findings we were able to explain both the depth and breadth of the issues our users faced. This time also gave us the opportunity to build rapport with our participants, allowing us to see parts of the process that were troublesome or difficult that they perhaps might not have shown us otherwise.

For example, staff told us that one of the systems they used ‘talked’ to the printer. We initially assumed that there was some sort of integration. In reality, though, the ‘talking’ involved downloading the files from the system and uploading them to a shared network drive. This was so common that for the police this was how systems ‘spoke’ to each other. This was an important realisation – that how we might understand a process might not actually be the reality, and a reminder that observation was just as important as communication.

Our findings

Having spent considerable time with the police, across different contexts and environments, we were able to produce a set of findings that not only showed the errors that were occurring in the system we’d been asked to investigate, but the physical workarounds that had been established to counteract the system. One of the headlines from our findings states that missing functionality and integrations with the system means police are forced to use slower, manual processes.

Through our research, we were able to show that staff used other, easier to use systems to complete tasks that the system in question was intended to enable. We also found that manual inputting played a significant part in the processes, and sometimes involved government departments who didn't have permission to edit the information on the system, this meant that they were having to regularly contact the police to ask for updates to be made on their behalf. These findings enabled our stakeholders to understand how systems and processes were intertwined, and make better, informed decisions to improve the end-to-end journeys of our users.

Do you have any tips on contextual research? Let us know in the comments.

1 comment

Comment by Anuar Bolatov posted on

Thank you Amy for sharing your knowledge and experience with the community.

It was a good read.

Regarding the question about tips on contextual research, I personally found that master-apprentice technique and using users own language while interviewing them helps me in the field research.

I'm looking forward to read more of your case studies.

Kindest regards,

Anuar