Members of the GDS user insights community were lucky to participate in a workshop on designing and researching with people with aphasia, run by Steph Wilson and Abi Roper. Steph and Abi work together at City, University of London in an ongoing collaboration between the Centre for Human-Computer Interaction Design and the Division of Language and Communication Science. The collaboration started in 2010 to research how to design for users with aphasia. Their work includes the INCA project, which is investigating how to empower people with aphasia to create, curate and access digital content through innovative technologies.

Aphasia is a language impairment that can affect speaking, reading, writing and understanding. It is often associated with motor difficulties affecting the use of the right hand. But it is not the same for everyone.

One in 5 women and 1 in 6 men will have had a stroke by the age of 75. One third of stroke survivors will live with aphasia. It can also be caused by other kinds of brain injury.

If you can’t read, how can you access and use the internet?

At the workshop, Steph Wilson gave an excellent example to help us empathise with how aphasia can affect a person. She changed the language of her Twitter account to Bulgarian – a language she does not read or speak – and was not able to switch it back to English as she didn’t know what any of the buttons or links meant. This gave us an insight into the impairment, which affects language but not intellect.

Sharing real life experiences

The workshop was attended by Ben, Lynn, Ian, Colin and Sian who were our aphasia advisors. They live with aphasia or are the carer of a person with aphasia. The advisors, with the support and guidance of one of the workshop organisers, shared their experiences of what tech they use, what they like about it and what aspects of tech and digital make their lives more difficult. Their honest, funny and revealing accounts were extremely powerful in helping the community gain insight into their daily digital lives.

One issue that came up was something many of us will be familiar with – remembering lots of different passwords. Time limits for sharing your details – which are there for security purposes – can be a real barrier when people cannot do it fast enough online or over the phone.

Some of the advisers told us that automated systems on the phone can be helpful. Others wanted to speak to a human being to make the experience easier.

Another issue that came up were changing interfaces. When a page has a different look or layout, it can feel like starting again and learning a whole new thing, which can make the experience of using the service more difficult.

Working with aphasia advisers

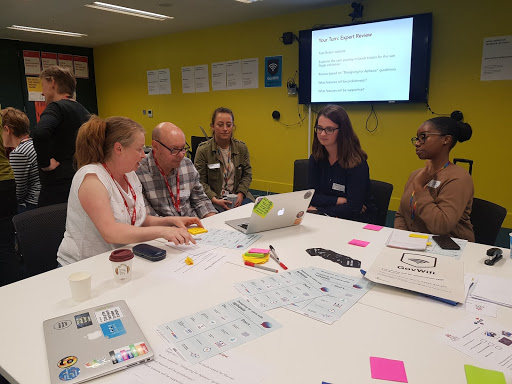

In the next part of the workshop, we worked with the aphasia advisers to do an expert review of an art gallery’s website. The task we looked at was booking 2 book tickets for an exhibition. We wanted to see - looking at what worked well and what didn’t work so well for them.

What can help?

Things that are particularly helpful to those with aphasia are in line with the content style guide that we already use on GOV.UK. They’re also in line with the guidance on accessible information produced by the Stroke Association.

Users will aphasia will find it easier to access information and services online, when:

- the language is simple

- there is not too much writing on one page

- there is consistency –across services and over time

- they can enlarge text for both reading and writing

- the layout is clear

Other things that help users with aphasia include:

- having multiple ways to do things. For example, one of the advisers who attended the workshop couldn’t complete the online DVLA application so they went to the post office instead

- icons being used with descriptive labels

- being in charge of the pace of interaction and not experiencing time-outs when it takes them longer to access or provide information on a page

It was enlightening to find out that many of the advisers did not know how to change the accessibility settings on their phones and tablets to make things easier to use. Often, accessibility options, such as ‘speak aloud’, might be more directly targeted towards users with low vision – though they may serve to benefit those with reading difficulties too.

Top tips for doing more inclusive research

One of the key lessons we learnt is that any research done with people with aphasia should be considered a collaboration – you are working together to look at the issues a service or product has. You are not designing ‘for them’ or doing research ‘on them’ but working ‘with them’ to make services more inclusive.

If you are working with a person with aphasia in a research session, it is useful to have a pen and paper at hand to help the conversation. This will allow you to write down key words, and draw diagrams or pictures to help explain things.

Best practice in usability testing of saying one thing at a time (for example, don’t ask multiple questions in one go) becomes particularly important. It's important that you both feel comfortable – take things slowly, be patient and don’t rush.

Also, don’t pretend you understand. Ask if you haven’t understood something that has been said. It can be useful to recap what’s been talked about to make sure you have a shared understanding.

To make the research sessions as comfortable as possible, reduce background noise, do the research in a quiet place – it helps people concentrate.

Finally, don’t be afraid to ask what helps. The charity Connect has great advice for talking to people with aphasia.

Thinking about inclusive usability testing more specifically, there are a few top tips for working with people with aphasia, which I share below.

Research prep

When preparing for a user research session:

- make sure you have plenty of time to run the research session but also be aware it can be very tiring – be prepared for that

- send consent forms for people to read before the session, and read them out loud at the beginning of a session. This is to make sure people have understood how the findings from the research will be used

How to ask questions

To ask questions effectively:

- support your questions with images and gestures

- ask one question at a time

- use concrete concepts in questions – be specific

- have yes/no prompts and printed rating scales to help people answer your questions

- in background interviews, use visual prompts, for example, images of tools they might use

Support participants doing tasks

To make the most of your research session, support your participants with the tasks you ask them to do. You can try:

- making your task a cooperative activity. This will make people more comfortable and help ease the potential fatigue of taking part in the research

- using concrete concepts, not wireframes but high fidelity prototypes because they are easier to understand

- supporting tasks with images and gestures which again support people’s understanding and how they communicate

- asking your participants if they have used the service before. If not, the session can be very challenging, and you might need to do a demo first

- when getting feedback after a task, go through the steps taken to complete the task again to make the things you are talking about concrete, rather than asking people to visualise and remember what happened

- not using task scenarios or role play. Instead, ask them to use the service for themselves

- avoiding conventional think aloud – have a natural conversation instead

Research analysis

When analysing your research findings, explore the task as a team, record what’s done independently, what’s done with support, and what’s not done at all in your analysis.

You can read more about making services inclusive in the Service Manual.

1 comment

Comment by Nikaesh Rattan posted on

Aphasia is a language impairment that can affect speaking, reading, writing and understanding. It is often associated with motor difficulties affecting the use of the right hand. But it is not the same for everyone.

University of London in an ongoing collaboration between the Centre for Human-Computer Interaction Design and the Division of Language and Communication Science.